The Angola Field Group looks forward to bringing you the latest developments from Cangandala National Park and Luando Special Reserve with monthly updates and photos, on what’s happening with Angola’s national symbol, the Palanca Negra Gigante or Giant Sable. Pedro Vaz Pinto, the man who re-discovered the Palanca Negra Gigante after Angola’s 27 years of civil war, heads up the Conservation Program to protect this animal which is on the list of the world’s critically endangered animals.

Scroll down or click on the links below to read the English and versão Portugês versions of Pedro Vaz Pinto’s reports. All photos and text © Pedro Vaz Pinto.

-

- 2020: 2020 Report (scroll down)

- 2019: Second Trimester 2019 Report, First Trimester 2019 Report and Capture Operation

- 2018: First Trimester 2018 Report, Second Trimester 2018 Report

- 2017: Second Trimester 2017 Report, First Trimester 2017 Report

- 2016: Third Trimester 2016 Report, Second Trimester 2016 Report, First Trimester 2016 Report

- 2015: Fourth Trimester 2015 Report, Third Trimester 2015 Report, Second Trimester 2015 Report, First Trimester 2015 Report

- 2014: Fourth Trimester 2014 Report, Third Trimester 2014 Report, Second Trimester 2014 Report, First Trimester 2014 Report

- 2013: First Trimester 2013 Report, Second Trimester 2013 Report, Special Capture Operation Report – July, Third Trimester – Final 2013 Report

- 2012: Fourth Trimester 2012 Report, Angola Field Group Presentation Video & Notes, Third Trimester 2012 Report, Second Trimester 2012 Report, First Trimester 2012 Report

- 2011: Third Semester 2011 Report , Second Semester 2011 Report , First Semester 2011 Report, January 2011 Third Trimester Report

- 2010: October 2010 Third Trimester Report , July 2010 Second Trimester Report, November 2009 to April 2010 Trimester Report,

- 2009: September & October 2009 Report , July & August 2009 Report, June 2009 Report, May 2009 Report , March/April 2009 Report , February 2009 Report , January 2009 Report

- 2008: December 2008 Report, November 2008 Report, October 2008 Report, September 2008 Report , August 2008 Report, July 2008 Report , June 2008 Report , May 2008 Report

- Read “Hybridization following population collapse in a critically endangered antelope”, an article published in the Scientific Reports published 6 January 2016. Authors: Pedro Vaz Pinto, Pedro Beja, Nuno Ferrand & Raquel Godinho.

- Download a revised and updated e-book edition of A Certain Curve of Horn – written by journalist, conservationist and artist John Frederick Walker

- At the end of this page you can read a selection of recent articles about the Giant Sable

- Click on small map image below to see protected areas in Malange province, the only place in the world where the giant sable is found. The small red area is Cangandala park, the large red area is Luando Reserve:

2020 Report

VERSAO PORTUGUES

Dear friends,Crazy year, with less to document than usual and for this reason only one annual report was prepared and is hereby presented. Due to the global pandemic, and more specifically to the measures adopted by most governments in the world in attempting to crush it – Angola being no exception, field activities were severely constrained. For several months I could not travel to the giant sable areas, and this hiatus covered the entire dry season, precisely the most important period to develop field work. I had never been away from the parks for such an extended period in at least the past 15 years. A hugely frustrating situation. Having several sables carrying GPS satellite collars and therefore tracked remotely from home provided modest compensation, but at least allowed me daily to keep a sort of ethereal link with the animals in the bush. Crucially, we were able to ensure the rangers’ routine work with the least possible disruption and communications were always maintained. Nevertheless, some important work could not be carried out, such as the reinforcement and amelioration of the remote ranger outpost. We had new equipment such as solar panels and batteries, but we could not get additional items and deploy the stuff to the bush before the first rains, so effectively and in this respect one full year was lost.

The extraordinary events of 2020 are also threatening to take a huge toll on the giant sable conservation, which may be nefariously affected in different ways. Most notably, there is an immediate contraction in economic activity which has caused some of our more reliable and long-lasting donors operating in Angola, to announce that they may not renew their contributions and even previously agreed commitments have been put on hold. But possibly even more worryingly, the economic strangulation is obviously much increasing the strain on people’s livelihoods, which in turn makes the prospect of adopting illegal activities such as poaching, more attractive and in some cases unavoidable. Sure enough, an increased poaching pressure has already been felt and is a major cause of concern these days.

Our ranger Mulundika with shotgun apprehended from poachers.

Adding to all our headaches in 2020, the previous rainy season and for a second year in a row, turned out to be very mild and we ended up facing a severe drought arriving early in the dry season and persisting until recently.

In Cangandala National Park, we were unable to monitor the herd on site throughout the whole of the dry season, which stopped us from recording breeding indicators and much hindered our understanding of the ongoing social dynamics. This was not so much of a crisis in the sense that all giant sables in Cangandala, except maybe some odd escapee, are contained inside the 4,400 ha fenced camp and at least reasonably well protected. So, unless there was some emergency happening, the herd should be progressing relatively well. In Cangandala, and generally, no news is good news.

It wasn’t until early October when I was finally able to assess the situation and track the sables on the ground. First rains had already started in Cangandala Park, and the animals were less approachable than usual, likely a result of many months of “abandonment”. They had understandably became less accustomed to people, and reacting a bit more nervously on the approach of the white Land Cruiser. But this was half-expected, and can soon be reverted. The visit coincided with the peak of breeding season, when sable bulls are most active and tend to converge towards and around the female herds. However, and unlike the previous breeding season when we observed one very large herd concentrated together and comprising of the majority of the female stock and including most bulls orbiting around them, on this occasion it appears that the females were dispersed into smaller-sized groups, and each dominated by a single bull. Difficult to say if this was a temporary arrangement or an inevitable step on a naturally evolving dynamic as the groups tend to break when the herds become larger in number. I’m inclined to believe it was probably the latter and facilitated by increased antagonistic behaviour among females and/or bulls’ insisting and aggressive efforts to chase and isolate some of them.

Interestingly, the oldest bull Mercury was in top form and clearly in charge of one group and apparently undisputed, when at the same time last year he was under a lot of pressure from very impressive younger competitors that seemed to be more aggressive and well capable of overtaking him as number one. And we were able to also find a few young bulls, some hugely impressive, apparently stabilized on new territories.

Vicente, very self-confident and imposing at just 5 years of age.

It suggests that most of the breeding season action may had already taken place, including some skirmishes between bulls, and therefore hierarchical relationships might be relatively stabilized in the sanctuary. Of course, this was just a very limited snapshot, a week of data after months of absence, and we are surely missing most of the data to build the narrative. Still, we know for a fact that at least some clashes have definitely turned violent, as the rangers found in July a relatively young bull, estimated age 5, killed as result of fighting – he showed clear signs of having been speared by the horn tips of another bull. It was an unfortunate but quite unavoidable event, and at the end of the day, a natural phenomenon that helps the populations to regulate their numbers while selecting for the fittest, strongest and more driven bulls to pass on their genes to the next generation.

Remains of a young giant sable bull that was killed by an intolerant older bull in Cangandala.

In Luando Reserve and failing the opportunities to monitor the herds properly in the dry season, we were able nevertheless to return in late October, and this time focused on trying to assess the condition of the herds, hopefully by filming them with drones, something we had done successfully in the past but not since 2017. That would only be possible thanks to the kind and enthusiastic participation of Jorge Ferreira, who came along with us and by bringing his drones and skillfully piloting these in the bush.

Jorge preparing the launch of the drone in an attempt to fly over a given giant sable herd, which had been previously tracked by GPS satellite, and triangulated from the ground via VHF telemetry.

It should be stressed that this operation could only be feasible because, contrary to the norm, rains had not yet arrived steadily by then in Luando, which following a very pronounced dry season, allowed us to make progress with vehicles outside the few existing roads. The plan relied on our team, which included the head of the law enforcement unit Fox and four more rangers, driving cross-country for about one week with two Land Cruisers and three bikes, to assess the mostly remote core areas of each of the five free-ranging giant sable herds in the reserve.

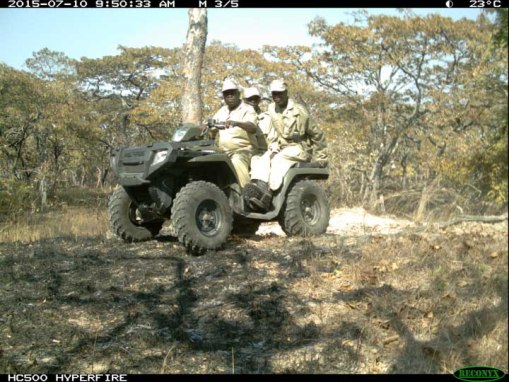

The rangers proudly display their bikes before we initiate our surveillance mission.

Although, and thanks to the daily GPS collar tracking over several years, we now have a pretty good idea of the home range of each herd, the areas covered by them are quite extensive, without access roads and the often thick bush makes visibility poor. We would maintain daily communications via satellite phone, to be informed of the most updated positions for a given herd recorded by the GPS collars. Usually, it took at least four to five hours (one day in practical terms) of off-country driving to get to each of the herd’s area, where we would set camp for the night. Early in the following morning, we would get the latest GPS position and make an approach to track and pinpoint the location of the herd by using VHF telemetry while keeping a “safe” distance estimated at around 500 to 1,000 m; once the first signal is picked, it becomes a straightforward process to do the triangulation. The final push would be sending a drone and trying to locate the herd from above and filming them for a while. Hopefully, this should give us updated metrics on the herd composition and recent breeding success over last couple seasons, etc. The droning process could take several hours, and if successful in filming the herd, we would return to unpack camp and drive off towards the site of the following herd, otherwise we tried again in the afternoon or the following day.

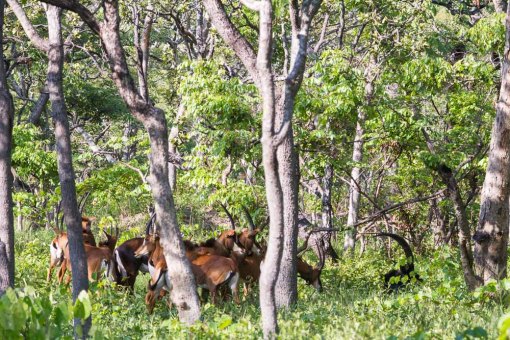

We have only five sable herds in Luando, and because of collar malfunction we lost contact with one of the herds – precisely the one in which only one cow had been collared, soon after it was marked. For this reason, we left this herd for last and focused on the other four groups. We did a poor approach to the first herd, which got spooked and forced us to postpone operations to the following day, but by then they had moved to a much thicker woodland. We eventually managed to film this herd with the drone, counting some 12 animals, but no conclusive data was possible to retrieve, because the tree canopy was dense and because we suspect that the herd being disturbed had split in two smaller groups. The second herd was a hugely disappointing experience, especially more so because we were dealing with the putative largest giant sable herd, numbering 40 animals in 2019. After some effort in locating and doing a proper approach, we then got the drone to fly over them in near perfect conditions, and we shot what we believed then to be beautiful and fairly long sequences with the animals in open ground. Great stuff, except that when we downloaded and tried to play back the films, we were shocked to realize that all the files were corrupted and were subsequently confirmed as non-recoverable! All effort was wasted, except for what we could see from the drone’s bird eye view in real time and which suggested the herd was healthy and probably numbered in excess of 35-40 individuals, including calves. We also did not succeed in obtaining footage from herd 03 but for very different reasons: after several unsuccessful attempts to visualize them from above following ground-triangulation, and during a short lunch break, the herd actually crossed at short distance an open savanna area right in front of us, which allowed for a fantastic sighting and a reasonable count. The group comprised of 21 individuals, plus the usual bull, which corresponded to a slight increase from 19 counted in the dry season of 2019. A herd increase of roughly 10% is within expectations. The fourth herd gave us some good footage, even though it was also a short sequence as they were a bit nervous and we located them with the drone running at low battery. We could only count 22 animals, which is a reduction from 27 recorded in 2019, but it is quite possible that we missed a few sables, especially calves. Overall, and strictly based on our footage and ground data, we believe the situation has remained broadly stable in terms of population numbers. Finally, we had to abort the survey of the fifth herd, as it was located in a much more remote region and without GPS tracking it could prove very difficult to find, but the main reason was that one of the Land Cruisers was overheating due to the radiator becoming clogged with grass and the weather was threatening rainstorms at any moment soon… so we decided best not to push our luck!

A new visit was made in November hopefully to try and approach sables again in Luando, but in the meantime the rains, although arriving late had by then started to fall with intensity.

-

Well into the last rainy season, the water overflowing and flooding roads and grasslands in Luando, making progress for rangers very challenging even with bikes (Photos by Fox).

To make things more complicated, construction works to improve the old roads connecting the main villages inside the reserve were being executed, but the result of these actions was pretty much the opposite. By enlarging the roads and throwing in layers of uncompacted red clay, it was possible to transform narrow and tortuous but well-compacted old roads, into very wide mud tracks where under the rain our vehicles attained as much traction as in an ice-skating ring. I ended up stuck near the main village, and the only way to make progress was on foot or in bikes, and be prepared to endure tough wet and muddy conditions. Field work was very much hampered and trying to approach the herds was out of the question. All I could do, was to enjoy a few days in the bush and spend some time photographing plants and smaller-sized fauna.

Bubbling kassina (Kassina senegalensis), more often heard than seen.

Common flap-necked chameleon (Chamaleo dilepis) on a ground journey.

Almost exclusively ground-dwelling Bocage’s tree-frog (Leptopelis bocagii) – following months of concealment buried in the ground, these tree-frogs “explode” in visible numbers by sprouting out of their hidings immediately after the first heavy shower in September or October.

As referred earlier, poaching is still a major cause of concern in Luando, and this in spite of our growing efforts in recent years in strengthening the law-enforcement reach and effectiveness. Of course, poaching is an illegal activity that may never be eliminated, and its incidence is also a dynamic process responding not only to the relative success of our combating actions but also to external factors such as the demand for bush meat and influenced by socio-economic pressures. Given the very serious and partly pandemic-linked economic crisis that we are experiencing in Angola, it is not surprising that we believe to have detected a surge in poaching activities intensifying during 2020. During the course of the year, various poachers were intercepted or detained, and several shotguns apprehended. Crucially, and following the work initiated in previous years, we were able to keep the most important water holes well-secured from traps throughout the dry season. There is little doubt that the herd access to water points in the dry season is when they are at the most vulnerable, and we have long concluded that intense poaching with snares in these strategic sites for several years in a row was probably the single most important mechanism that led to the collapse and near extinction of giant sable in the post-war period, and even more so than the indiscriminate use of firearms. On the other hand, this is not to say that snares don’t still pose a serious threat, and the fact remains that rangers regularly come across “snare lines” – these typically consist of relatively straight artificial blockages arranged with bushes and cut trees crisscrossing the woodland and extending in length for a few hundred meters, in which every 20 to 50m an “opening” is made and duly trapped with a steel-cable snare attached to a 6m long flexible pole cut from a small tree.

Snare line in which we dismantled 16 traps, was found well within the grazing area of one of the sable herds.

These “snare lines” are usually placed in such a way that they surround patches where the grass was deliberately burnt a few weeks earlier to attract ungulates to the fresh regenerating grass. Such a system can be highly efficient throughout the dry season and during the early stages of the rainy season. Although we believe that sables are generally wary of these traps, and we actually witnessed one of the herds making a 90º turn in front of us to avoid crossing a snare line, this learning is surely acquired at a high cost. To illustrate this point, just a few weeks prior to our encounter with the herd and the referred snare line, the rangers had tracked down and observed one cow belonging to this group, with a severely injured leg and not far from the site.

Ranger setting out for patrol in distant areas in Luando Reserve, preparing for several days outing (Photos by Fox).

The battle continues.

Best wishes,

Pedro

P.S. Photographic records and a couple sequences from drone footage can be accessed via the following links:

https://photos.app.goo.gl/BLkAcYqaBp4hEUKXA

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1UKTwwjGo3nar4jyHd5F5_7XVsb2i2eiq

- Second Trimester 2019 Report

VERSÃO PORTUGUÊS

Dear friends,Following the July aerial operation implemented in Luando Reserve, we kept ourselves busy throughout the remaining second half of 2019, which included the reinforcement of anti-poaching activities and the remote monitoring of collared sables in Luando, but notably we also carried out a darting and collaring exercise in Cangandala in October.

Looking back, we have moved a long way in Cangandala National Park, sixteen years since our first hesitant and quite unsuccessful on-foot survey. By then we weren’t even sure if giant sable had survived the civil war, and it took us a few years to conclude that only a few old cows were left, and all males had been poached in the park. Ten years have now passed since a bull from Luando reserve was flown from Luando to join the surviving nine females in a fenced camp, and nine years completed since the first little calf was born to mark the start of the new era. Being a male, the calf received the name of Mercury, a roman god of communication, travelling and soul-guiding, and also the planet closest to the sun. A lot of hopes and responsibility was laid on Mercury’s shoulders, but over the years he has certainly risen to the occasion, becoming the master bull in Cangandala and making a significant contribution to the breeding success of the local herd.

We estimate the current numbers in Cangandala to be around 80 animals, all still confined inside the 4,400-hectare sanctuary. All evidence and observations suggest that the herd is doing extremely well, as inferred by physical condition of animals, breeding rate and success, low mortality, and no indications of overgrazing or excess of antagonistic behavior. The last breeding season appears to have been exceptional, and quite well-synchronized, which likely reflects an ideal life cycle and we may interpret as the result of good conditions and adequate management of this population.

Calving peaked in June, and it was quite rewarding to observe in July and August, the formation of a large crèche with many young calves of similar age. This crèche comprised at one stage 20 little ones, which may well be the largest concentration of giant sable calves ever recorded. Adding a few off-season births in subsequent months, gives us good reason to consider 2019 as hugely successful year in Cangandala! Remarkably and confirming previous experiences, the giant sable herd seemed to be quite relaxed and tolerant of our presence when the calves are young and in crèches. The group-behavior appears to give them extra confidence, and even if the calves are still very vulnerable. This is in marked contrast with the period of May/ June, just before and during calving, when females tend to isolate themselves and generally become much more wary, and often not tolerating approach.

September/ October coincided with the onset of the annual breeding period, when males are increasingly more excitable, and females get in estrus. During this period, we witnessed very interesting behavior in Cangandala, some of which somewhat unexpected or at least not text-book material, but quite consistent with drone footage that we had obtained in Luando in previous years. This had mostly to do with the behavior of bulls and how they evolved and interacted within the herd. Instead of an increased fighting among males and dominance behavior that could be expected to lead to an inevitable situation of having one dominant bull removing all contenders from the herd vicinity, and being therefore more exclusive than during the rest of the year, we actually have is a bit of the opposite. We found all males present and cohabiting the same area, including the large master bulls, the younger territorial contenders and even the much younger from bachelor groups. It seems they all converge to the herd and orbit around the breeding cows. Sure enough, they’re not exactly all friends and there are obvious dominance rituals in play, but yet they manage to behave in a much more peacefully fashion than one would think considering their fierce reputation and being in the presence of those beautiful and receptive females. One can clearly see a hierarchy very well established, but everyone seems to know their rank, and its as if they’re not really interested in wasting energy in fighting with the bounty so near. Instead, it’s more of a free-for-all situation, with various bulls trying to corner different cows according to their rank, and we see even very young males sneaking around females when the other bulls are distracted.

This provided an opportunity for us to keep track of many bulls and younger males, including the majority of individuals born in the first few years of the program and some we had not seen in a long time. And we came across no males injured or in bad physical condition. I believe this deconstructs the notion that it is not possible nor advisable to keep more than one bull in a fenced camp with females because various males will waste too much of their focus in fighting, affecting breeding efficiency and will eventually kill each other. On the contrary, I believe that, at least providing the camp is big enough in size and the habitat conditions ideal, keeping the bull population increasing naturally can be beneficial, as the dominance hierarchy is likely an important selection tool to keep functioning which does not necessarily ends up in tragedy and may even stimulate breeding. Besides, it may also distribute the breeding opportunities across a larger number of males, thus maximizing genetic diversity and in a fair (and naturally selected) way. At the end of the day, it is likely that the exceptional breeding success and remarkable calving synchronization may be at least partially correlated to a healthy competition among existing bulls. If there is a lesson to be learned here, is to keep things natural as much as possible. Providing ideal natural conditions, from habitat to keeping social structure, appears to be the way to produce the best results!

Another “natural” development had to do with Mercury’s role in the herd. Assuming that he had been performing well as the main breeding bull for three to four years, we had decided it was probably a good time now to alleviate him of this burden. However, and much to our surprise, by observing the social interactions during the breeding season it became apparent that he had moved down the ladder, being now number three in the bull hierarchy! Not only his younger sibling Eolo is the current number one, but the number two position is now taken by an even younger bull, we estimate around seven years old, and tentatively identified as Ramses, a male we had lost track of a few years back.

Surprisingly the herd was now being controlled not by Mercury or Eolo, but by a younger, yet quite impressive male – Ramses.

There is still another very large bull and a serious contender for number one in Cangandala, which we saw a couple times far from the herd and apparently not interested in challenging the established hierarchies, and possibly it will be another “lost” bull, Apollo. As for Mercury, in truth he didn’t seem too concerned or demoralized for having been demoted, not even he behaved like a defeated or vengeful bull. He was still as imposing and noble-looking as ever, transmitting the serenity and authority of a true leader, except when Eolo or Ramses approached and lowered their horn tips, in which case Mercury would calmly relinquish his position and move off calmly. Mercury still behaving as the herd bull most of the time, but it’s also as if he feels that it is not really worth it to challenge these young, powerful and testosterone-inflated bulls.

One cause for concern was observing one female with a very serious limp, which was clearly reflecting on her physical condition, and had very recently recently calved.

This female had a badly injured left hindfoot which she constantly licked, and she often stayed behind and struggled to keep up with the rest of the herd. Our previous experience in Luando demonstrate that leg injuries are frequent, but pretty much always caused by snares set by poachers. Would it be possible that there were active snares being set inside the sanctuary in Cangandala, even though we’re dealing with a fenced camp which should be reasonably well-patrolled regularly? We couldn’t believe that! Maybe, an alternative scenario could also explain the injury, like some sort of localized wound followed by infection… we followed the female a few times and took plenty of photos, but the cause remained inconclusive. We would need to dart the poor cow, and the opportunity would present itself in October during the second collaring operation in 2019.

We had initially intended to dart and move a small group of animals, including Mercury, from the main sanctuary to a new smaller camp and destined for tourism. However, frustrating delays in finishing some complementing yet crucial components, such as water hole and support and observation infrastructures inside the camp, adding the start of the seasonal rains, made it unadvisable to translocate these animals in October. On the other hand, we were concerned with the fact that our VHF collars were reaching the end of their battery life, which could soon make regular monitoring and future darting exercises much harder. All considered, we decided too still carry out a darting operation and focusing on marking animals and deploying new VHF collars. As always, and to implement this highly specialized veterinarian effort, we enjoyed the privilege of having Dr. Pete Morkel and this time co-adjuvated by Dr. Charlotte Moueix. We had also a reinforced support team present throughout the operation, with rangers and young researchers from Kissama Foundation.

The plan was to try to approach the herd from the Land Cruiser to dart the animals and deploy up to seven VHF collars, including females and bulls. Charlotte would do the shooting and Pete supervise all veterinarian procedures. We felt confident that it would be possible to approach and dart the first few animals, but if the animals started reacting and responding nervously it could prove difficult to dart more than a few individuals.

The first animal we darted was Nicole, the poor six-year-old female that was limping. Unfortunately, our worst fears were confirmed… she had been victim of a poaching incident, and still carried a steel cable deeply wrapped inside her foot!

It was a nasty injury, and with a cable knot tightly stuck between tendons, it took Pete and Charlotte more than one hour of stressful hard work, to remove the cable. Shocking, terrible stuff. Still, she was duly treated and should make a full recovery now. We estimate the poaching incident to have occurred less than six months ago and, of course, the worst part is now knowing for sure that there is active poaching with snares going on inside the sanctuary. It is hard to ignore that this sort of action in such a supposedly well-protected site, is likely done by locals with the participation or complicity of rangers, so this is a highly sensitive matter which we hope to tackle in the near future. Subsequently we darted a second female that also had been victim of a snare, although it had likely been a nylon rope more than one year ago and she had recovered well. Nevertheless, it proved we weren’t dealing with an isolated incident.

Other than the recorded injuries, the operation went extremely well and beyond our expectations. The darting went like clockwork, as we were always able to approach the herd and Charlotte didn’t miss one shot. Typically, the first Land Cruiser would approach first and dart one sable, which would soon go down calmly near the herd, and we would then park the two vehicles as to semi-block the view and handle the individual, often only a few dozen meters from remaining animals which pretty much ignored our presence. In just a few days we darted a total of nine females and seven males, all measured, photographed and ear tagged. We were able to deploy our seven new VHF collars and recycled two old units. All animals were sampled for future DNA-extraction and we were also able to obtain biopsies from ten additional individuals. We expect this way to fill in the blanks on our studbook and much improve our knowledge on how the diversity of the genetic pool in Cangandala is evolving. Although we didn’t immobilize the two older bulls, in general all males were very impressive, giving us the impression that successive generations of bulls are growing larger and with more powerful horns, possibly as result of increased competition? The largest horns measured were those of Ramses, at 54.5 inch horns, but a young 3-year-old male carrying 46.5 inch horns was equally impressive.

In Luando reserve and during this second semester we focused our attention in remote monitoring of the animals and anti-poaching on the ground. Having sables with GPS collars that can be tracked permanently has proved an invaluable source of information on their habits and movements and ultimately on stepping up their security. In July we had deployed two GPS collars on females in each of the five existing herds, except on the fifth herd (KI) that was only located on the last day of the aerial operation and for this reason in this case we could only mark one cow. In addition, six collars had been used on males, two on young animals in bachelor groups, and four on territorial bulls. Unfortunately, we have been facing some technical problems, and four collars ceased transmitting data before end of December, including precisely the two collars deployed on the young males and the one used on the only female collared in herd KI. The areas were thoroughly patrolled by the rangers soon after the collars stopped working, but we found no signs of foul play, so it was likely malfunction. A bit disappointing the fact that, once again, we lost track of the most elusive of our five herds. To make things worse, it is the largest herd and its home range is possibly in the now less secured area… pity. In compensation, the remaining herds are being very well monitored, and we could even observe interesting group splits in two of these herds, that occurred during the breeding season and have been maintained since. We might be witnessing for the first time how and when new herds are formed, but in alternative the split may also be explained by seasonal changes in the social dynamics. It will be fascinating to keep track of these movements over the next few months. As for the males they’ve been pretty much behaving as expected. One of the males is a herd bull and stays most of the time accompanying the cows, while three others appear solitary and were holding territories not too far from herds.

In order to increase our anti-poaching response, we have installed a brand-new military tent in the advanced post in Luando, and we have also purchased a solar-powered system with solar panels and batteries to be installed on site. Resulting from poaching incidents and poachers that were intercepted by the rangers, two motorbikes, three bicycles and two shotguns were apprehended.

Best wishes,

Pedro

Photos can be accessed through the link: https://photos.app.goo.gl/991JsFdosLnUPKs18

_________________________________________________________________

- First Trimester 2019 Report & July Capture Operation

Dear Friend,

July Capture Operation

In July we carried out the 2019 aerial capture operation, another crucial milestone and the corollary of many months of preparation. Resorting to specialized game capture team, including veterinary services and helicopter rental, it was the fifth such exercised implemented in 10 years. As in all previous operations, the key role on the team was played by our good friend Dr. Pete Morkel, one of the most experienced wildlife veterinarians and a legend in his field.

Just as in 2016, the pilot was Namibian-based Frans Henning. Unlike the previous exercises though, this time we could not hire a Hughes 500 chopper, the machine of choice for this job with our particular conditions. As alternative, we rented a Jet Ranger Bell 206, a somewhat larger, powerful and highly efficient and reliable chopper, but lacking the maneuverability of a Hughes 500.

We take here the opportunity to thank our main sponsors, namely (alphabetically): Angola LNG, ExxonMobil Foundation, Segré Foundation, Tusk Trust and Whitley Fund; and also smaller, and some in-kind, but relevant contributions for this operation, received from: Ecotur, Geigert family, NSCC, Oceaneering, Safari Enterprises and Step Ahead. We also recognize the role played by INBAC and the Provincial Government of Malanje in ensuring support at various levels, and, as always, a very special acknowledgement is due to the Angolan military (air force and army), who have assisted with fuel, logistics and organization details. Finally, we must also thank some individuals, who provided crucial support in organizing, advice, networking and logistics, namely Carlos Cunha, Genls Hanga, Sousa and Traguedo, and the Schaads (David and Ruth).

The 2019 capture operation was to focus exclusively in Luando Reserve and had pre-set the following main objectives: 1) an updated census of the giant sable population; locating the five known existing herds and, through a detailed photographic record, evaluating population demographic parameters such as sex ratios and age structure. 2) dart up to 20 giant sable and deploy up to 15 new GPS/Iridium collars and, if necessary, a few additional VHF collars; ideally, we wanted to put two GPS collars in two females on each of the five herds, and five GPS collars in bulls. 3) an assessment on threats, especially focusing on poaching evidence; an effort was to be made in visiting most of the water holes, and when appropriate, take action against poachers. As an extra, last minute addition, we would try to put a lion GPS collar if, during our operational flights, we were to be given such opportunity.

The operation went exceptionally well and almost all objectives matched our expectations. The only relevant shortcoming was that the lions didn’t come to the party, when none was spotted even though we did make a bit of flying over the areas where they had been last recorded. It would have been nice to dart and collar one lion, a first for Angola, but we knew it would probably be very unlikely and it wasn’t our main focus anyway. In brief, the operation was a huge success! In total, we darted 17 sable and deployed all our 15 GPS collars, distributed in nine females and six bulls.

No casualties, or incidents affecting the health of local animals as result of our actions, was to be recorded. Un updated survey was concluded, plus detailed demographic data and threat assessment.

We collared four mature bulls, presumed territorial, and one of them was accompanying one of the herds.

The territorial bulls were chosen randomly, and their estimated age was six, seven, eight and 12 years old, the latter, Ngola, had been darted but not collared in 2016. All these mature bulls were very nice healthy specimens, with average horns that measured between 52 and 56 inches in length. The largest specimen seen, however, was photographed twice in the first few days, but we didn’t have the chance to dart.

One magnificent territorial bull, surely the most impressive seen in 2019, but which we could not dart.

We also came across several bachelor groups – dispersing young males tend to aggregate in small groups for some time before eventually becoming solitary and establish their own territory. The bachelor groups seen had between two and seven males, of ages three and four.

An amazing bachelor group with seven beautiful young males of ages 3 and 4 years old – one would be darted later on.

Although we’ve never done it before, this year we decided to collar two four-year-old bulls from different bachelor groups. They were both very nice powerful young specimens, with horn lengths between 46 and 48 inches. There is quite some risk involved here, as these young boys may roam aimlessly and easily get in trouble – they are surely more vulnerable animals to poaching or may also be killed by older bulls. On the other hand, by tracking a four-year-old we hope to detect and document the moment when they settle down and become territorial, a phenomenon that is still poorly understood. Regarding the bulls, the biggest surprise, by far, was finding Bruno alive, a bull that had been collared in 2013 and then estimated to be around 12, which would make him today 18 years old!

To our surprise we found and darted Bruno, a bull now at the estimated age of 18… he doesn’t have much more time to live; we removed his 2013 collar and wished him a peaceful ending.

Considering that we had never found a bull older than 15, this was quite a shocker. We darted ol’ Bruno and relieved him from his battered neck collar. As one would expect, he was in terrible physical condition, and most of his teeth were worn out down to the gums. He must not have more than a few more months to live… we let him go and wished him luck!

Always fascinating to report on the bulls, but the females are the crucial component, and we were eager to tackle the herds. The first four herds were relatively easy to locate and at the end of the seventh day of flying we had collared two cows on each of these herds, plus a couple territorial bulls.

The fifth herd (named KI), however, proved much harder to find, but very much like in previous exercises. This is the herd that occupies a home range furthest from our base of operations and furthest from the other groups, but it also the one for which we hold less information. Although this is one of our two largest groups and located in a region characterized by extensive anharas (natural clearings) and relatively open woodland, for some reason we tend to struggle in finding them. In 2009 and 2013 we couldn’t locate them, while in 2011 we found only a very small subgroup that had temporarily split, and in 2016 we only got them on the very last day of flying. In addition, we have also been unlucky with collars, as the only two GPS collars we managed to put in this group in the past, lasted only a few months before one collar broke and in the other case it was the female that died. The last remote data from this herd is more than two years old. As result, our knowledge about the routines of this herd is relatively poor when compared with remaining herds. To make things worse, even one additional VHF collar left in 2016 is missing in action (cow likely poached). So early on, we started looking for herd KI, but without much luck… we kept finding bulls in the region but not the females! After several consecutive days and many hours of relentless searches we came to the last effort on the very last day of flying… and that’s when we found them! This was a relief, but just like in 2016, by then we had only one GPS collar left, so we darted two cows and the second was released with VHF only. Now let’s hope we get better luck with these collars!

Comparing 2016 and 2019 demographic data for the five herds, we estimate a population increase of roughly 15%, which I consider a fairly good result. True that a well-protected healthy population could probably grow at a rate of 15% annually, which is how the Cangandala herd is performing, but given the insecurity in Luando and empiric data reporting the continuation of poaching activities, we feared it could be much worse, and even a population decrease could not be ruled out until we now pulled this survey. Equally important was determining that the demographic parameters in terms of age structure and ratios in every herd are now much better than ever recorded in the past 10 years. In short, the number of cows have remained stable or even reduced slightly, but in compensation the average age of females has dropped and the number of yearlings and immatures has increased significantly.

These parameters suggest a much healthier population, with a higher potential for growth in the short term, and one that appears to have suffered a lot less pressure from snaring over the last three years. As we had documented previously, snares affect primarily young animals, and were responsible for an unbalanced population with skewed age structure, when we had more old females than younger ones, and few yearlings made it to adult classes. During this survey, the age of darted females averaged seven years old, and only one cow was estimated to be over 10 years.

The impact of traps can also be inferred from scars carried by survivors.

In previous operations, the average of injured individuals among darted animals has been calculated between 20 to 25%. These have always included specimens with either extremely nasty leg injuries, such as with signs of necrosis or amputated legs, or active wounds that forced Dr. Morkel to perform emergency surgical procedures in the bush to remove ropes and steel cable snares, etc. In 2019, three handled animals had leg injuries, corresponding to roughly 18%, but on this occasion the wounds had healed and the incidents that caused them were estimated to have occurred several years ago. Also, two of the affected individuals – one bull and one cow, were older animals with estimated age of 12, and only the third was a eight year old female. So, the fact that the general population is now on average younger, and yet the older animals carry a much larger proportion of injuries when we know for a fact that young animals are the most vulnerable, is a very encouraging result because it is consistent with a recent reduction in poaching.

We did find less signs of poaching than in previous surveys, and not surprisingly, the herds closest to our new advanced post within the areas that have been patrolled more efficiently, are the ones that show the clearest increase in numbers! This not to say that there were no worrying signs. Especially in the region where the furthest herd resides – KI, and which have been rarely patrolled by our rangers, poaching was still rampant, and we found plenty of traps around water holes.

Although possibly less than in previous years, poaching is still a major concern in some areas, where the water holes were often full of traps aiming to catch sable.

Some of these traps were clearly targeting the giant sable herd, situated within a few hundred meters from where we eventually found the group, and also evidenced by the use of huge poles with steel cables or very large iron gin traps.

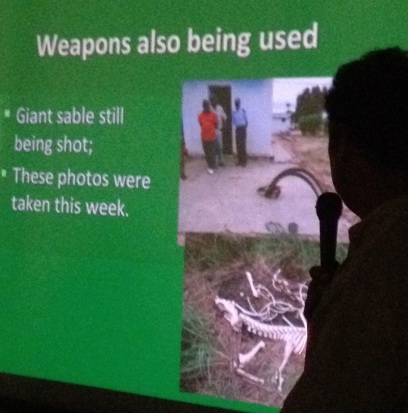

We cleared these sites, and a joint incursion with military for anti-poaching was prepared and will be carried out in subsequent weeks. On the other hand, and although we concluded that poaching with snares around water holes – the most damaging method, has been possibly efficiently eliminated in the regions where we have based the rangers, still we did find some poaching camps and it appears that here the poachers are now mostly resorting to nocturnal hunting with spotlights and shotguns.

Overall, the situation seems to have improved, and not only the giant sable population show a perceived increase.

Two other species in particular, appeared much more common than in any previous survey, the roan antelope and the reedbuck, which were easily recorded and daily. It is likely that they are responding well to the increased security in the reserve, and this probably also helps explain the resurgence of lions.

First Trimester 2019 Report

Not only the rains had initiated late in the last quarter of 2018, but they also ended early this year. Although there was plenty of localized variation, with some sites actually receiving a lot of rainfall, in most areas the rain had stopped by mid-March and soon after it had become apparent that we should prepare for a drought in the dry season.

In Cangandala things have remained relatively quiet, with the animals well adapted and protected inside the main sanctuary. The improvements to finalize the construction of the new tourism sanctuary were delayed due to bureaucratic issues and may well compromise the initial plan of translocating in the dry season the bull Mercury with couple young females, as part of his retirement package. Following several years of being the dominant bull, Mercury needs to give way to younger contenders. Of notice in this period, was the arrest made by rangers, of one poacher that had killed one waterbuck in the south of the park.

Regarding Luando we had started the year still battling with the consequences of the December poaching incident, when three poachers who our rangers had arrested red-handed with the remains of a freshly killed giant sable female, were shamelessly set free by the judicial system. Although in the previous report I blamed a judge for the unfortunate outcome, that was an incorrect statement. Instead, they were sent home by a local prosecutor with whom the poachers and respective families, managed to negotiate a friendly release. This of course raises some worrying issues regarding the conduct of local police authorities, but also means that the incident is not necessarily closed from a formal legal standpoint. We have since been trying hard to follow through the process at higher level, and we still hope the poachers will be called back and receive the well-deserved exemplary punishment. At the very least, we need to ensure that a similar chain of events will not happen again!

At least the incident stirred the waters and we felt poaching was temporarily reduced in Luando. On the other hand, it took some effort but we managed to maintain the advanced post with permanent ranger presence throughout the whole rainy season, now completing one full year. Reaching the post to ensure supplies and ranger rotations proved increasingly difficult as the rains progressed and the landscape became flooded, so we had to open alternative routes. In any case this was a crucial achievement, allowing us to much extend our effective security reach and establish a permanent presence within close distance to three of the five local giant sable herds. Before end of the year we expect to much reinforce this post with better equipment, such as a brand new military tent and a solar kit. In the future, possibly during 2020, we expect to expand further our presence by opening a new service tracks and establishing a new advanced post, but first we need to strengthen our management and logistics capacity.

At the end of first semester, still four GPS collars were still active and about to complete three years of work, which is quite remarkable. These included two collars in territorial bulls and another two in females, although the latter were both on the same herd. These collars proved instrumental in allowing us to better understand the whereabouts and behavior of giant sable, and much improved surveillance and targeted security.

If poachers appeared to reduce their activity markedly in our increasing area of influence, the most significant happening was the unexpected return of four-legged predators: lions! It had been a few years since our last recorded evidence of lions, but they now finally made a comeback. The first event took place in early June, when our three rangers based on the advanced post spent a sleepless night subject to the mighty roaring of a male lion. A lion roar can be a frightening experience as it triggers a visceral sense of fear in human beings, and this can be worse when heard for the first time ever. Our rangers are still inexperienced in many respects and for them a lion is a creature of tales, of which they had never seen, heard or smelled! They were totally unprepared, and it is therefore not surprising that they panicked, and then, against better advice, one even made random shots into the woods at night! In the words of one of the brave survivors: ‘- when the lion roared the ground trembled beneath our feet”, and ‘- the roaring was so loud that the leaves were falling from the trees all around us!’ So, a lion male was back! But, remarkably, and even more striking experienced was reserved for another ranger team a couple weeks later, when two rangers that had left the camp for a routine patrol, stumbled onto a pride of lions chasing bushpigs! They saw a male, a lioness, and four cubs. This is the first evidence of resident lion breeding in Luando for many decades! Needless to say, that the rangers got the scare of their lives. They made a hastily return, while setting the grass on fire on their rear. The return of lions can surely pose some risks to the giant sable herds, but it is likely a reflection of the increase in wildlife populations as the local ecosystems may be recovering some of its lost functions. In any case, this new development was most unexpected, and brings up a new set of challenges and opportunities that we expect to tackle in the future.

Best wishes,

Pedro

Photos can be accessed through the link:

https://photos.app.goo.gl/UZ7qyRVGHC8c4H4J9A short video can be accessed here:

https://photos.app.goo.gl/m3y8i2jmkAX7ZvKK7

Quite common in the giant sable areas, this leaf-toed gecko appears to be a yet undescribed species and is the subject of ongoing research.

_________________________________________________________________

-

- Second Trimester 2018 Report

Dear Friend,

Second half of the year is typically busier for us on the ground than the previous and this one was no exception. As the dry season progresses and eventually gives way to a spring-of-sorts shortly followed by the early rainy season, the conditions on the ground tend to be the most favourable in terms of our own mobility, while the local ecosystems evolve in remarkable fashion.In July the climate is dry and harsh, the early mornings can be very cold and we witness the last seasonal wild fires; the landscape looks desolate and is marked by the burnt colours mostly greys, black and browns, there is no grass and the naked trees seem deceivingly moribund; this a time when sable cows have just finished calving and the herds reunite and are drawn to the anharas. During August the trees start regenerating the leaf cover and new grass is sprouting in pockets while the days are typically very hot, dry and windy; it is a good time to observe the sables, when the herds feast on the new grass and the little calves can be seen in créches.

September is the closest we have of a spring, characterized by a spectacular explosion of colours in trees and bushes, from light greens and yellows to deep reds; this is when the skies start accumulating clouds and energy and may release the first odd discharges.

It is also the period when bulls become increasingly agitated, challenging each other and moving great distances in search of receptive cows. In October we witness the first serious showers, but these are still very irregular in space and time; the breeding season has reached its peak and bulls remain nervous and excitable. During November the rains finally set in, becoming more frequent and generous, and this is when the bright colours fade and give way to the deep greens; bulls are now exhausted, they isolate themselves and have ceased the harassment of females. December can be considered a typical wet season month – the first of a few more to come, the grass is now well developed everywhere, the soil muddy and waterlogged, and a homogenous green blanket covers the landscape; the sable herds tend now to move deeper into the woodland but spending long periods in smaller areas, while bulls will routinely re-attend and patrol their territories.

In Cangandala we were able to testify once again the excellent results of the previous breeding season, confirmed by the large number of young healthy calves, which were often observed in créches. But possibly the most striking note the abundance of young males that can now be seen, forming several bachelor groups spread across the sanctuary.

Some of these males are quite young, under three years of age and having recently abandoned the respective herds, but others are reaching six years old and are quite handsome, even though they’re not yet ready to challenge Mercury, the resident territorial bull. As the mature and self-confident bull he is, Mercury is a pleasure to watch, as he is very tolerant of our presence and often allows the LandCruiser to approach to within 30 meters.

However, his dominant status can’t be taken for granted anymore and he is spending more time patrolling the territory and less time accompanying the herd. The main reason for his increasing restlessness is surely the presence of Eolo, who’s becoming stronger and more imposing by the day. Mercury is being challenged and by the end of the year it was no longer obvious who was the number one in Cangandala. In fact, one way or the other, Mercury’s retiring time is approaching fast, as we intend to move him in 2019 to a newly built sanctuary.

The recent appointment of a warden in Cangandala NP has proved very beneficial, improving general management in the park and culminated with the detention of a group of local poachers. These were caught while carrying bushmeat from several duikers and bushbucks killed in the park. The poachers were well infiltrated in the local villages and we have reason to believe that they had been doing their business for a few years with total impunity.

It is in Luando reserve, however, that most of our work is focusing these days, and where the tasks are more challenging. But here is also where our progress is becoming more significant. Our recently-appointed head of rangers for Luando, senior ranger whose war name is Fox, is doing an excellent job in training and organizing the sable shepherds and turning them into functional rangers. Our actions are finally having a direct impact in terms of law enforcement in the reserve.

The first crucial tasks that we had devised was fully implemented during this period. We opened up several bush roads and built an advanced ranger post 50 kms into the bush. This camp is situated on a scenic spot near a major temporary stream and a permanent lake, strategically close to three of the five surviving sable herds, and consists of a large tent placed on dry ground under the shade of large Brachystegia trees. Here we stationed teams of four rangers on two-week rotations. In the absence of radio repeaters and cell coverage in the reserve, we keep daily communications via satellite phones. The rangers keep motorbikes for routine transport, and logistics have been ensured weekly, initially by LandCruiser, and by quad bikes since November, when the rains made local roads impassable for regular vehicles.

By using this new post as an advanced base, we were able to penetrate much further in routine patrols and reach critical spots that required investigation. One of our first missions was rescuing two GPS collars from animals we knew had died a few months earlier. We had remotely tracked one bull and one female as they stopped moving, which usually can only mean one thing: death. They should have been both healthy animals, the bull was nine years old and the female was quite young at six years of age. Mature bulls can often fight to death, but in the absence of natural predation, the death of a young female is always a major worry – not only we lose an animal of greatest potential for breeding, but it also is a likely indication of poaching. In both occasions simply by tracing the remote data, we could only infer the death to have been sudden and without warning, so it was inconclusive as for the cause. Ideally, we should have been able to react immediately after the events were identified, but unfortunately it occurred in a very remote location and during the rainy season, and we lacked resources to react promptly. We had attempted a couple previous incursions but failed to reach the sites, which were relatively close to each other. Now that we finally got there, we were shocked to confirm that the female had indeed been poached and it was actually dismembered and smoked on site, and the poachers had camped there for a few days and didn’t even bother to destroy the collar or hide the evidence.

Intervening and recovering evidence on a poaching camp where a giant sable female was dispatched and smoked.

Very sad indeed, and we had arrived too late. We also recovered the collar and remains of the bull, but could not determine any obvious cause of death. It may have been a natural death, nevertheless, being a mere 4 km from where the female was killed is very suspicious, and it appears very likely that both animals were shot by poachers.

We believe, however, that from now on, we are better prepared to react immediately on future alarming signs obtained from GPS tracking, and reach most critical locations within 48 hours after an incident occurs and is detected. We are on standby at the moment, with a permanent team deep in the bush, with transport means and communications in place.

An unusual incident happened in Luando, when local witnesses reported the sighting of an allegedly “ill” big bull that entered some agricultural fields near one of the main villages in the reserve. This was somewhat unexpected as it took place in an area quite far from any recent confirmed records of giant sable. A team was sent to the site and the bull was located, but it had died a few hours earlier. Upon inspection it proved to be a very old bull, and there were no signs of foul play, and nor even fresh injuries that could suggest he had recently battled another bull.

On the other hand, his body condition was poor and his teeth were almost completely worn down to the gums. In all likeliness, this bull must have died of old age, unable to feed as his teeth lost their function once and for all. He was an old warrior with only one horn, as the other had likely been long lost in battle. Still, it was a very respectable horn, well-arched and measuring 57 inches long. Being found relatively far from the remaining sable population is consistent with it being a dispersing old bull, who has lost his fair share of skirmishes and may have been now looking for a quiet retirement spot to end his days.

The step-up of ranger presence and anti-poaching measures produced measurable results in several occasions throughout the past few months. Apart from localizing various temporary poaching camps that were duly destroyed, on one given patrol in October, a group of three poachers were intercepted near a camp site. These poachers managed to escape but their bicycle, ammunition and one shotgun was apprehended.

In their camp we found remains of duikers and warthog. However, we were still preparing for December, a month that is reputed to be the one most preferred by poachers, eager to enhance their earnings before Christmas. Every year it is claimed that poaching reaches a peak during December, so we wanted to be ready this time, and our senior rangers sacrificed their family obligations in favour of staying in the bush without interruption from mid-November till mid-January. And this bold move would produce results!

Benefiting from preliminary undercover intelligence work and with firm collaboration received from local villagers, we were informed in early December, that a serious poaching team had crossed the Luando river and was operating in a given region. The area in question happened to be the most remote location in relation to where our bases are established, and yet too close to our largest giant sable herd. This herd is therefore the more vulnerable, as it occupies a home range about 30km away from the next nearest group, and for this reason it has remained less protected. We reacted by sending our six best rangers to survey the area and prepare an ambush if possible. Sure enough, six poachers were intercepted and following a few shots fired, three got away but the other three were detained, plus one weapon, ammunition and three well maintained motor bikes. Significantly they were carrying various animal parts and remains and included the skin of a giant sable female. This was simply the first time in 50 years that poachers are arrested with evidence of killing a giant sable! Upon interrogation, the poachers confessed killing the giant sable in the previous weekend and reported that the smoked meat had already been sold and sent to local markets in the neighbouring province of Bié. They were returning to resume their activities when we caught them.

The success of this operation was a major achievement, and the rangers were very proud and motivated, and even the local villagers cheered the arrest of the trespassers. We had reasons to be optimistic, but unfortunately, despite all our efforts, subsequent events were to be a shocking disappointment and to cast a dark cloud over the current situation. Although we worked in close collaboration with provincial authorities, government, police and military and we thought that all the necessary steps had been taken to make sure the poachers would receive exemplary punishment, the judge ruled that the poachers should be released upon paying fine of AKZ 250,000.00, which was worth less than US $250.00 per person. This was a ridiculous amount, and worth much less than what they had already profited from selling the bush meat! This ruling blatantly ignored that the act of killing of a giant sable – our natural national symbol, had recently been criminalized and the fine set at the very impressive and dissuasive amount of AKZ 22,000,000. And yet they got away paying only 1% of what the law recommends because the judge took pity of them or possibly didn’t think this was such a serious offense. Needless to say, this was huge blow to the morale of the rangers, and even the local villagers feel frustrated and revolted against the judicial system. We are now trying to minimize the damage, and hopefully use this as leverage to force changes that may take effect in the future.

Best wishes,

Pedro

Photos can be accessed through the link:

https://photos.app.goo.gl/vFMgziEbUhWDZwoq7_____________________________________________________________

-

-

-

-

- First Trimester 2018 Report

-

-

-

Dear friends,

The new year started as it had ended the previous one… wet, very wet! And so continued until the very late end of the rainy season in May. After the drought in the previous year and seasons, the generous rains must have been quite welcomed by the animals, and allowed the regeneration of critical functions within the local ecosystems, by promoting abundant regrowth of the vegetation and replenishing of the water table, with streams and dry rivers coming back to life, filling of water holes and inundation of floodplains. These were excellent news and make us feel and make us feel optimistic for the ensuing recovery of sable populations, but didn’t exactly make our lives any easier on the ground, in terms of field monitoring. Indeed quite the opposite, and this was especially troublesome in Luando Reserve, where progress was slow and critical activities had to be put on hold for a few months.

In Cangandala, the copious rains gave way to abundant grass, a lot of grass really, tall, thick, and everywhere. In the end of May the soil was still too moist and the floodplains full of water, and by mid-June, when we finally could venture the LandCruiser off track, a thick wall of grass made it a nightmare for us to make progress, and the unavoidable tiny grass seeds released in millions quickly clotted the radiator, in spite of double protective nets.

Explosion of grass making progress a nightmare in May and June.

It happens every year, but this season was worst than usual, started later and was more prolonged in time. But anyway, in the park things are simply going very well and at cruise speed. Sable are breeding exceptionally well, they are well protected and the area of the sanctuary is still big enough to sustain a fast growing population. We may have to consider in the future enlarging the full-protection area or releasing some pressure by moving part of animals, but these decisions may wait for at least a couple years.

Lots of young animals make the majority of the herd.

The long and intense rainy season has various and additional predictable consequences, one of which is that the controlled burnings and wild fires are likely delayed and less frequent. Probably a lot less surface will burn in 2018 both in Cangandala and Luando, although there is a risk that if the next rainy season is delayed, then the unusual accumulation of combustible material in the form dead grass may facilitate exceptionally severe wild fires in September, and these should be avoided if possible, particularly in Cangandala. Another not so good consequence, was that in the park we struggled to make preventive fires and controlled burnings to promote mosaic micro-habitats and regrowth of vegetation in strategic places, which tended to be highly favoured feeding spots by sable in the dry season. As the grass remained relatively moister than usual, very little was burned until end of June in the sanctuary. Still, we managed to partially burn some patches on the main floodplain and some small areas on a couple anharas, so these will surely become grazing and browsing hotspots for the animals shortly after in the dry season.

As result of the terrain conditions, we struggled to approach the sable herds in Cangandala, and the visibility was always blocked by the almost impenetrable wall of grass. In addition, the females were also quite dispersed and behaving shyly, surely a consequence of being calving or preparing to calve, or nursing their new-borns. We could confirm that Mercury was still routinely patrolling his favourite area, suggesting he still maintains an undisputed position of dominant bull. Nevertheless, we could testify that Eolo is definitely becoming more impressive by the day… his horns are beautifully arched and more imposing the Mercury’s, but he is also putting on weight and clearly appearing less slender and rather displaying a more muscular build, while showing a darker and shinier coat. It is probably a matter of time until Eolo challenges his elder sibling, and I suspect it may not take that long for him to become number one and the new master bull in Cangandala.

For Luando we had high expectations to increase monitoring and extend security measures across its vast wilderness areas, but the rainy season much limited our movements and as result various activities had to be put on hold. An effort was made in terms of increasing manoeuvrability, and a critical component was to solve the transport constrains. Throughout most of the rainy seasons it is impossible to drive a 4×4 vehicle off road in the reserve, and even the few main sand roads become quickly impassable, so the most efficient solution is resorting to bikes. In February we deployed three brand new Honda bikes, which we hoped would allow the rangers to reach remote locations in the bush, at least by driving through existing foot paths as penetration routes followed by foot patrols.

The brand new bikes arriving in Luando.

However, we had underestimated how wet the conditions would become this year, and soon after the bikes arrived it was evident that things would not work out as planned. Although the bikes are performing very well, they are not amphibious, and with the woodland becoming completely flooded in many places, the bikes had to be carried too often and long patrols turned into a nightmare.

Luando inundated in March during patrols.

This was disappointing, as we had to freeze some important activities, but on the other hand the generous rains are encouraging as they must have replenish by now all the temporary water holes and this might be crucial for the local breeding herds. A new plan is now on the works to be implemented in the dry season, which will evolve around building access roads and deploying advanced ranger camps deep in the bush. These camps will be reached with 4×4 vehicle in the dry season and quad bikes in the rainy season.

In spite of the described constrains in movements, the step up of security measures initiated in the previous year is producing encouraging signs. In particular, the semi-permanent presence of two senior rangers, well equipped and maintained, and fully motivated has been a game changer in the reserve. And the fact that our senior rangers maintain a direct link and have been endorsed by the Angolan military, give us additional strength.

Senior ranger Fox charging the sat phone and GPS with solar panels.

Although so far only minor offenders (small game poachers) have been detained, the senior rangers are already well respected and feared. The message is clear: the giant sable is a national symbol and sacred, so Government and partners want to take seriously the mission to protect the species. Surely there will be problems ahead, poaching is far from eliminated and poachers are likely lurking and readjusting to the increased pressure, but we feel we are finally getting a grip on the situation. With training exercises scheduled to the second semester we hope to further increase security on the ground.

In the meantime, seven animals, four males and three females were still being tracked via GPS satellite collars until the end of June, which was quite rewarding as these collars thus completed two full years operating, sending a GPS position every four hours. They may not last much longer now, but their impact has been extraordinary, by giving us in-depth knowledge and pioneering data on the biology and behaviour of giant sable, and by allowing us to pinpoint with extreme accuracy the home ranges of various herds, the latter aspect being critical to improve security.

Mercury with his collar.

Throughout the first semester we were able to witness how different bulls moved across their territories and interacted spatially with other bulls and herds, and we could even infer interesting breeding and calving behaviour in females.

A lot of activities are planned for the remainder of 2018, and will be dealt with in the next report.

Photos can be accessed at the link:

https://photos.app.goo.gl/Jrwc95p28s7CgFZ38Best wishes,

Pedro

_______________________________________________________________-

-

-

-

- Second Semester 2017 Report

-

-

-

Dear friends,

The year of 2017 was possibly the most atypical in terms of weather conditions that we have witnessed since the start of the project. A most severe draught caused by very little rainfall between January and March gave way to a prolonged and very stressful dry season, which in turn was followed by precocious heavy rains starting in September at full-throttle.

In Cangandala I have sad news to report: Ivan the Terrible passed away on July 10th 2017, inside the sanctuary.The death of an old warrior who lived a most eventful life. Here’s a synopsis of his bio: An imposing bull, massively built and scarred from battles at age 8 when we first found him in Luando in July 2011; was then darted twice, collared, flown inside a military MI-17 chopper, taken for a ride on the back of a pick-up and released inside the sanctuary in Cangandala; within one week upon release he killed a young innocent 2 year-old bull stabbing him several times, and soon after broke through the sanctuary fence and escaped; established his new territory in Cangandala outside the fence and showed little interest in joining other sable – social skills weren’t his strength; proved to be elusive as a ghost, never allowing approach from the ground, and eventually managed to break his radio collar; in May 2012 he fought the patriarch bull Duarte through the fence, leaving the latter in a pitiful state, badly injured and humiliated; but even after defeating the dominant bull Ivan didn’t take the bounty and apparently ignored the unattended females; in March 2013 challenged again the old bull Duarte, who had taken many months to recover, and once more a terrible fight occurred across the sanctuary fence but this time it must have been too much for good ol’ Duarte and he was never seen again – surely Ivan finished him off; in August 2013 we flew several hours with helicopter over his territory hoping to recapture him, but never got a glimpse; before the end of the same year he was victim of a snare trap that barely took his life – he was caught by the left front hock and must have endured immense suffering; throughout 2014 he was a shadow of the former Ivan, skinny and limping, he lost his jet-black coloration and his bravado; by end of 2014 however he seemed to have recovered to a relatively good condition, but then he mysteriously disappeared for over one year – we have no idea where did he go and at the time feared for his life; he resurfaced early in 2016, now apparently fully recovered, and then endured a couple skirmishes across the sanctuary fence with the bull Mercury; in July 2016 we darted him from helicopter and he was then released with a GPS collar; in March 2017 he went into a terrible battle again through the fence, and resulting from it he ended up moving into the sanctuary – after six years of freedom and adventure in Cangandala, he decided to return to captivity, where he finally died. R.I.P. Ivan!

His death appears to have been “natural” and peaceful, although we suspect that it may have been caused by the fight that resulted in his return to the sanctuary in March. At the respectful age of 14 and after having endured so many battles and life-threatening situations, he should have settled down, but I supposed that would have been against his nature: a life on the edge and always to the limit… in that sense one has to wonder how he managed to live this long! Our first suspicion was that he had last fought Mercury, but we have now concluded that most likely it was the latter’s younger sibling Eolo, age 5, who finally defeated Ivan, as he was established in a territory that includes the area where the battle took place. Poetic justice could be claimed as Eolo revenged the death of his father Duarte, which took place when he was just a few months old.

Eolo succeeded in completing the task where his two older brothers have failed – we know that Mercury had a few encounters with Ivan but they never came to anything, likely because Mercury was too smart (or coward?) to push things further; and Apollo has long disappeared without a trace, very possibly killed by Ivan.

Before recovering Ivan’s skull we placed a trap camera, and the absence of specialist scavengers in Cangandala became once again evident, when only warthogs visited the site to pick some rotten flesh and gnaw on the bones.

Sable breeding in the sanctuary is going exceptionally well and the population is steadily increasing. We have surely more than 60 pure animals at the moment and with a very healthy age structure – these days, calves and young make up for the majority of giant sables in Cangandala.

A malfunctioning water pump forced us to manually supply water in basins during part of the dry season, but the animals soon adjusted to the change and were often observed congregating around water. Mercury has assumed his leading role, and inherited the gentle nature, tolerance and serenity from his father Duarte, which exerts a relaxing influencing over the females, and is most convenient in allowing us to approach the herd at close range. We therefore achieved plenty of good group observations.